If you asked me to guess at the Venn diagram of people who like silent films and people who like video games, I would probably draw two entirely separate circles. But, as I've gotten into silent films over the past few months, I've realized that the medium that rose to prominence in the first 20 years of the 20th century has a lot in common with the medium that rose to prominence in its last 20 years.

Silent film, especially silent comedy, is built on iteration. A silent short, like Buster Keaton's One Week, takes an idea — "Newlyweds are gifted a prefabricated house in a box which they must assemble" — and twists and turns the idea repeatedly, throwing wrenches in the works for laughs and gasps. If you play a lot of video games, the structure won’t feel that different.

Most movie characters have emotional arcs, which is true in narrative-driven video games, too. But, the more potent arc in a video game is typically the player's progression from weak to strong, from empty-handed to fully-armed. As you travel along that path, games tend to surprise you with curveballs that change your approach to the game. They might be things that help — like Kratos returning to his cabin to get the Blades of Chaos in God of War — or they might be things that hurt — like temporarily losing everything in your inventory in Resident Evil 4 Remake — but the goal is to keep players guessing about the specifics of the story, even as they're likely to know it's overall trajectory. Yes, you end the game stronger than you started. But, what happened along the way?

Silent comedies, similarly, are more about the antics and gags the comedian cooks up than the overall arc of the story. Like many video games, these comedies are built around set-pieces. In Harold Lloyd’s fantastic short film, Never Weaken, the bespectacled comedian is inadvertently hoisted onto scaffolding high above the ground and must attempt to get back down. In Sherlock Jr., Buster Keaton plays a projectionist who, while dreaming, is transported into the films projected on screen, and through the magic of editing, travels to vastly different locales in the space of a cut.

These moments are especially exciting because they predate the more complicated digital effects filmmakers would use to accomplish similar shots by about 70 years. When Keaton is scrambling to get pieces of timber out of the path of a moving train in The General, he's actually performing those stunts in front of a train. It's good that labor practices have changed in the past century — John Wick director Chad Stahelski recently said that he wouldn't know how to pull off some of the things Keaton, Lloyd, and Charlie Chaplin did even today — but there is a thrilling tension in the danger on screen in these early films.

The kinds of movies that feel most like games (in a good way) are the ones, like silent films, that are built around setpieces. Jackie Chan’s Police Story series (and Hong Kong action, in general), the Mission: Impossible movies, heist films, and certain kinds of horror movies that revolve around elaborate kills — all of these deliver on something similar to the thrill a great video game level provides. They take an idea, explore it to the fullest, then move on to the next thing. Without sound or dialogue, silent comedies communicate the rules and stakes of a stunt or set piece, execute it, then keep going.

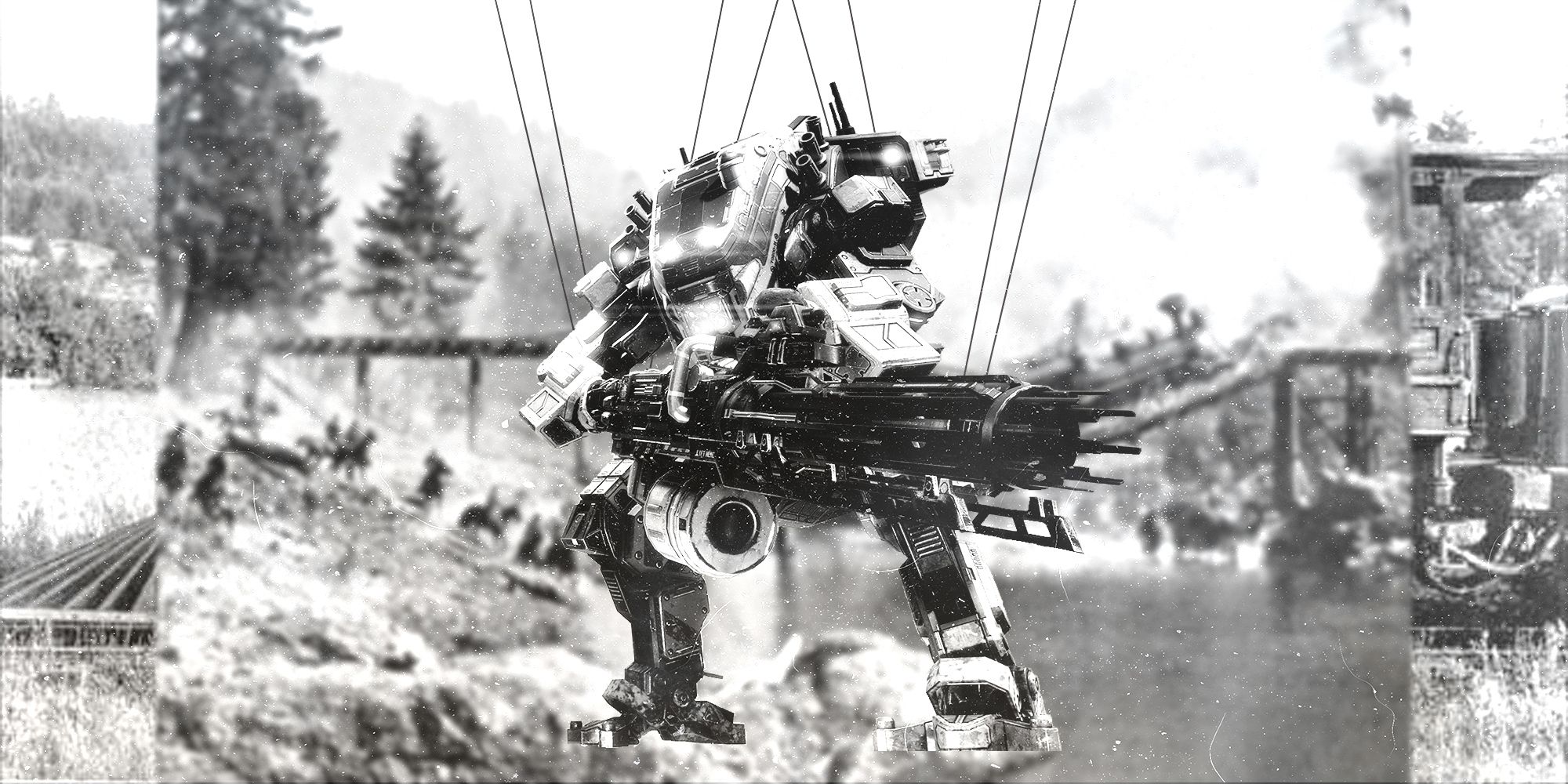

When I watched Sherlock Jr. for the first time earlier this year, it reminded me of Titanfall 2’s “Effect and Cause,” the level in which you get a device that lets you travel between two different time periods with the press of a button, sometimes needing to time your presses to the second as you wall run between the two different eras. It’s a magical piece of game design, and not so different from the magic Keaton discovered in the cut. If you love that feeling in games, many surviving silent films are in the public domain so you can watch them for free. If you're tired of waiting for Respawn to come back to the Titanfall series, see if Sherlock, Jr. scratches the itch.